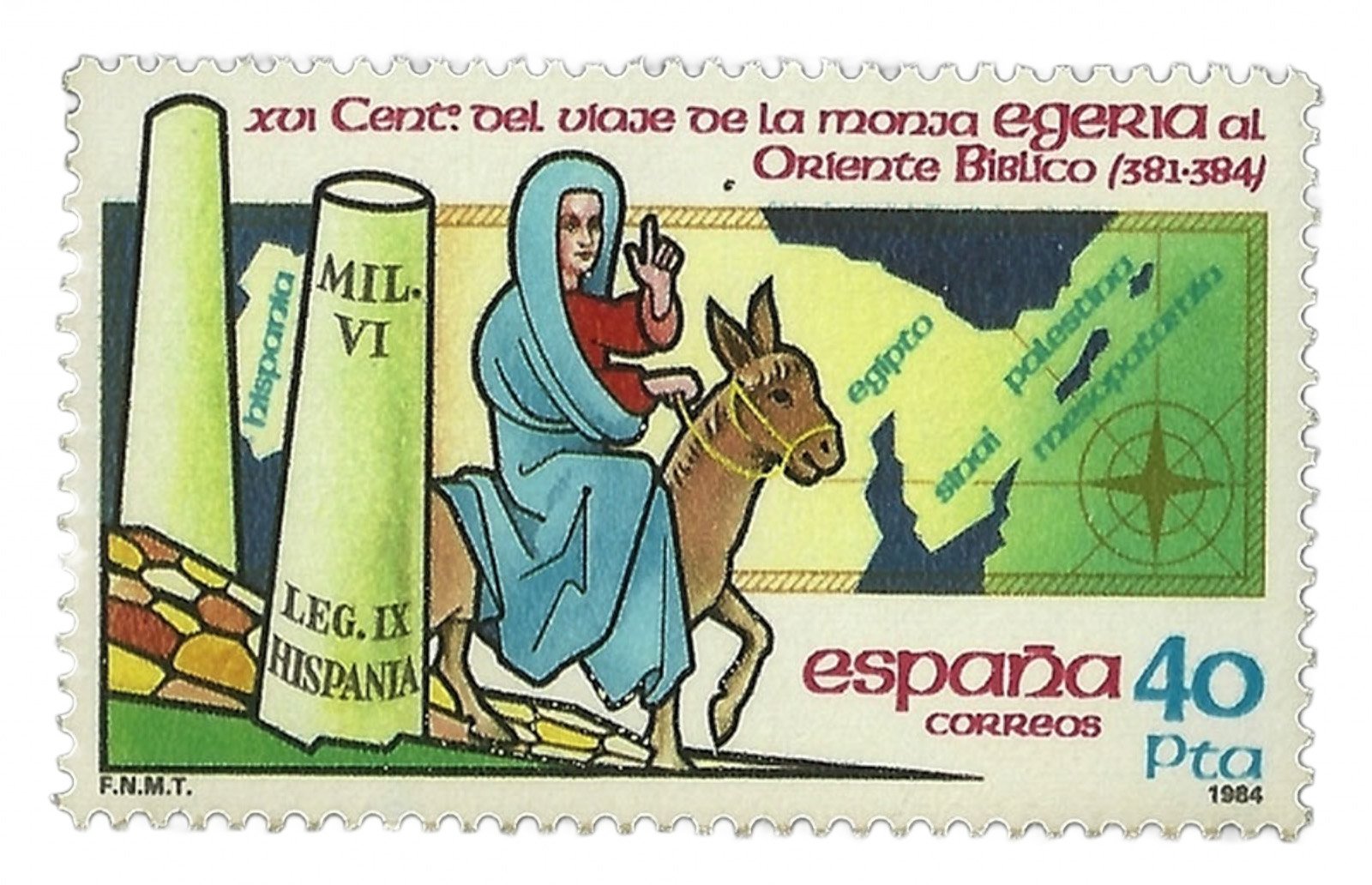

Egeria on the road — a Spanish stamp from 1984 commemorating the 4th-century pilgrim from Roman Hispania, whose letters describe her long journey (381–384) through the eastern Mediterranean in search of biblical places and lived faith.

In the late fourth century, when the Roman Empire was changing shape and Christianity was becoming its spiritual backbone, a woman from the far western edge of the known world set out on an extraordinary journey. Her name was Egeria. She came from Roman Spain—probably from Gallaecia (Galicia)—and she left behind something rare and precious: a first-hand account of her travels across the eastern Mediterranean and the Holy Land, written in her own voice.

Egeria did not travel as a princess, nor as a pilgrim escorted by armies. She travelled as an educated, determined Christian woman, curious about places, rituals, and people—and confident that she had every right to be on the road.

A Woman Who Could Travel

Egeria’s letters, often called her Itinerarium or travel diary, show that travel in Late Roman Spain was not reserved for men alone. Roads were maintained, hostels existed, and letters of recommendation opened doors. Egeria moves with surprising ease through a vast territory: from Constantinople to Jerusalem, from Mount Sinai to Mesopotamia, from Egypt to Asia Minor.

She travels slowly and attentively. She asks questions, listens to local guides, and records what she sees. Her tone is calm and practical. There is no sense that she feels she is doing something improper or dangerous simply because she is a woman. On the contrary, she writes as someone fully entitled to be where she is.

This alone makes her text remarkable.

Travel with Purpose, Not Escape

Egeria is often called a pilgrim, but her journey is more than a religious checklist. She does not rush from shrine to shrine. She wants to understand how places connect to Scripture, how local Christians celebrate feasts, how liturgy differs from one city to another.

When she reaches Jerusalem, she stays for a long time—not days, but years. She carefully describes Holy Week, Easter, and daily worship. Her interest is almost anthropological. She observes how religion is lived, not just where it is anchored.

This kind of travel requires time, resources, and social support. Egeria never explains exactly who she is, but it is clear that she belongs to an educated Christian elite—possibly a woman in a religious community, possibly of noble background. What matters is that her society allowed her enough freedom to travel, write, and be taken seriously.

Spain at the Edge, Not the Margin

Although Egeria writes mostly about the eastern Mediterranean, her Spanish origin matters. She refers to her homeland as distant but fully part of the Roman-Christian world. Spain is not a backwater in her eyes; it is simply far away.

Her letters were meant to be read back home, by a group of women she addresses as dominae sorores—“lady sisters.” This suggests a network of educated women in Roman Spain who were eager to learn, read, and imagine the wider world through her words.

Egeria is not writing for male authorities. She is writing to women like herself.

Practical, Curious, and Unafraid

What makes Egeria so modern is her voice. She writes in simple, clear Latin, closer to spoken language than to classical literature. She explains things patiently. She admits when she is tired. She notes when roads are difficult, when guides are helpful, when places are disappointing.

She climbs mountains because she wants to see where Moses stood. She visits remote monasteries because she is curious about how people live there. She asks bishops to explain things to her—and expects answers.

This is not passive devotion. It is active engagement with the world.

Freedom Within Limits

Of course, Egeria’s freedom was not universal. She could travel because she belonged to a specific social, religious, and economic class. Enslaved women, poor women, or women outside Christian networks did not enjoy the same mobility.

But within those limits, her journey shows what was possible. Late Roman Spain was part of an empire where women could own property, move independently, correspond across long distances, and participate intellectually in religious life.

Egeria’s letters quietly challenge the idea that ancient women were always confined, silent, or invisible.

Further Reading

Egeria. The Pilgrimage of Egeria: (A New Translation of the Itinerarium Egeriae.) Translated with introduction and notes by Anne McGowan and Paul F. Bradshaw. Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2018.