Title page in Greek and English of the chapter on ‘The Wars in Spain’ in Appian’s Roman History (written in the 2nd century AD).

Most people know Rome’s great enemies: Hannibal in Carthage, Mithridates in Asia Minor, or Spartacus in Italy. Far fewer remember that in the rocky uplands of Spain, Rome fought some of its longest, most humiliating, and most tragic wars. The story comes to us through the Greek historian Appian of Alexandria, who in the 2nd century AD wrote his Roman History. One section, simply called The Spanish Wars (Iberica), describes how, from the 3rd to the 2nd century BCE, the legions tried to tame Hispania – and how fiercely the Iberian tribes resisted.

Appian begins with Rome’s arrival in Spain during the Second Punic War (218–201 BCE). At first, the task was simple: drive out Hannibal’s Carthaginian forces. Scipio Africanus succeeded in that mission, and Carthage was expelled. But Rome decided to stay, and that decision drew it into decades of bloody conflict with the native peoples. For the Iberians, it was a fight to preserve independence; for Rome, it was a struggle to secure a rich and strategic province full of grain, iron, and, above all, silver and gold.

From the start, the Iberians proved a different kind of enemy. The Celtiberians, living in the rugged central plateau, fought in small, mobile bands. They harried the legions, struck from mountain passes, and disappeared into the hills before Rome could retaliate. The Lusitanians, further west, did much the same. Roman armies, trained for set-piece battles on open ground, repeatedly stumbled into ambushes.

Appian’s account lingers on two unforgettable episodes. The first is the story of Viriathus, a Lusitanian shepherd who rose to become a general without equal. Between 155 and 139 BCE, he led his people in war against Rome. Time and again, he outwitted the consuls sent against him, luring them into narrow valleys, cutting off their supplies, and melting away before superior numbers could close in. Appian tells us that Rome came to fear this man so much that, when they could not beat him in battle, they bought his own envoys to murder him in his sleep. With his death, Lusitania’s resistance collapsed.

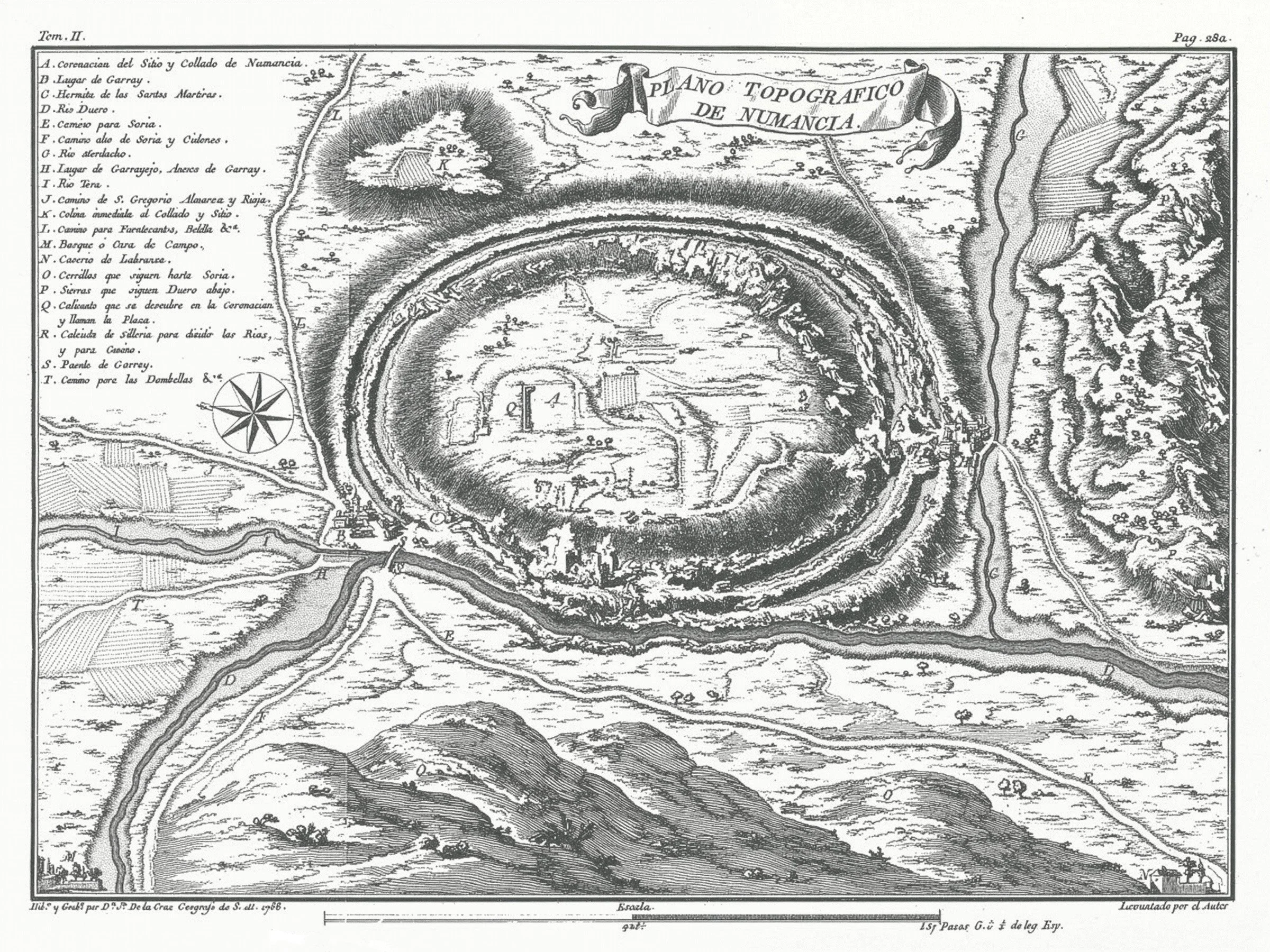

The second and even more dramatic episode is the siege of Numantia, the Arevaci stronghold in modern Soria. Between 154 and 133 BCE, Numantia became Rome’s nightmare. Generals and legions were humiliated; whole armies surrendered to the small hilltop town. Finally, Rome sent its most ruthless commander, Scipio Aemilianus – the very man who had razed Carthage to the ground. In 134 BCE, he surrounded Numantia with seven fortified camps and a system of ditches, walls, and watchtowers. Appian describes how he starved the Numantines into submission, sealing off every path of escape.

Inside the city, famine led to desperate measures. Some ate grass, others boiled leather; there are reports of cannibalism. Yet they refused to surrender. After almost a year, in 133 BCE, when all hope was gone, many Numantines chose suicide or burned their own homes rather than face slavery. Rome entered a silent, smoldering ruin. Appian’s stark lines capture the horror: the Numantines, he says, “preferred to perish in freedom rather than live in servitude.”

For Rome, Hispania was eventually secured – a province rich in mines, soldiers, and resources, essential to the empire’s future. But the cost was enormous, and the scars deep. For the Iberians, the wars of Viriathus and Numantia became symbols of heroic resistance, remembered centuries later by writers, poets, and even by Cervantes.

When you stand today among the ruins of Numancia, or in the hills where Viriathus once outmaneuvered legions, you see more than stones. You see the landscape of one of Rome’s hardest lessons: that conquest was never easy, and that freedom, for some, was worth more than life itself.

City plan of Numantia by Juan Loperraez (1788).

Further Reading

Appian, Roman History, Book VI (The Spanish Wars). Accessible online in English at Livius.org.

Appian, Roman History, Loeb Classical Library, vols. I–IV (Harvard University Press).

Schulten, A., Numantia: Die Ergebnisse der Ausgrabungen 1905–1912. Leipzig, 1914.

Richardson, J. S., Hispaniae: Spain and the Development of Roman Imperialism, 218–82 BC. Cambridge University Press, 1986.