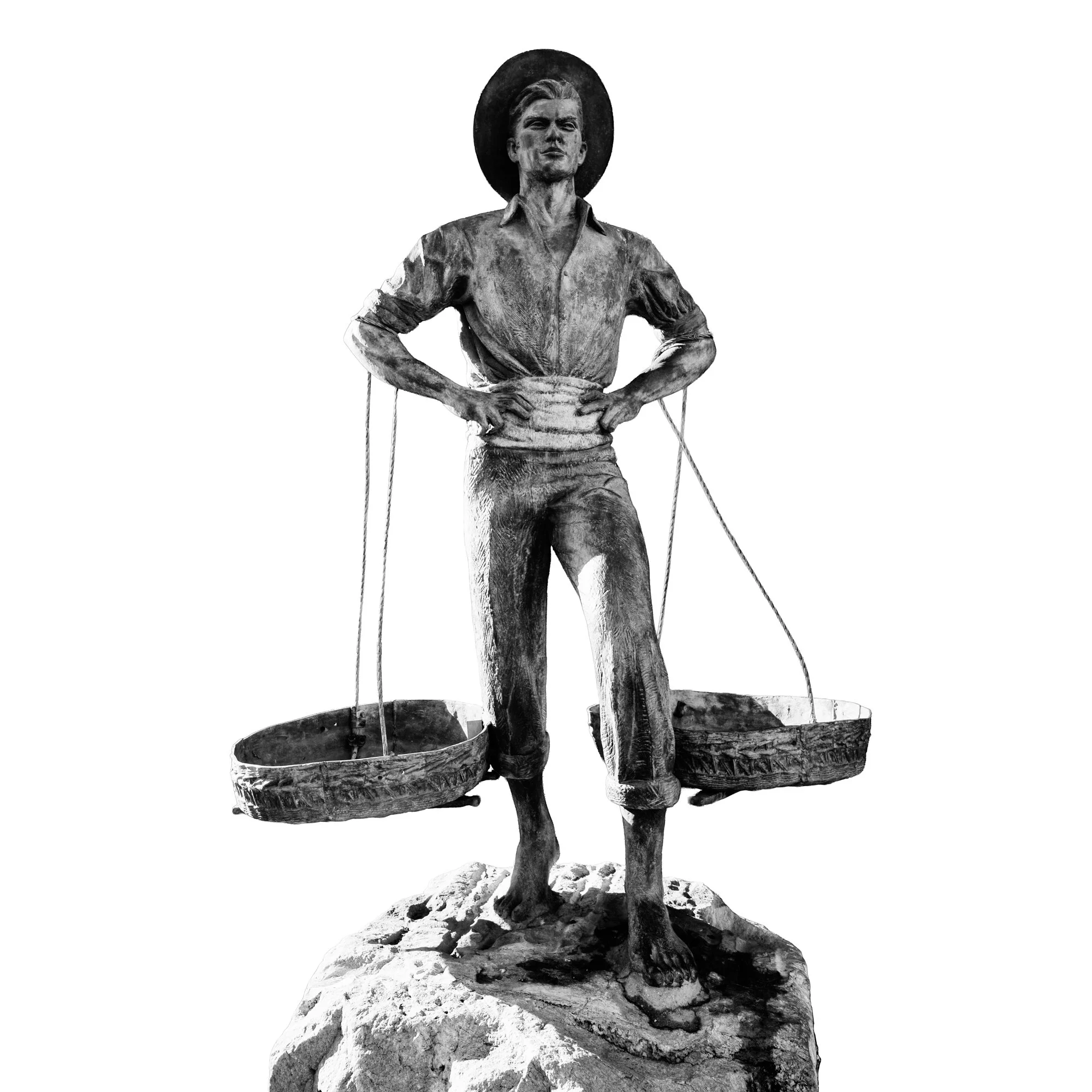

El Cenachero (Malaga, Spain).

At the edge of Málaga’s harbour, where cruise ships now glide in and out and tourists sip cocktails in the sun, stands a bronze figure with bare chest, strong shoulders and two baskets of fish hanging from a wooden yoke. His name is El Cenachero — and he is one of the most recognisable symbols of the city.

Long before Málaga became a destination of beach clubs and boutique hotels, it was a working port. Every morning, fishing boats landed their catch on the sand. From there, men known as cenacheros carried the fish into the city, balancing two wicker baskets (cenachos) on their shoulders and walking from street to street selling the day’s harvest.

They were not merchants in shops. They were moving markets.

With loud voices they announced their arrival:

“Boquerones frescos!”

“Sardinas vivas!”

The cenachero walked barefoot or in worn sandals through the heat, his skin darkened by the sun and the sea. His work was hard, his pay modest, but his role essential. Without him, Málaga did not eat.

The statue near the port is not a monument to a general or a king. It is a tribute to labour. To the men who turned the sea into daily bread. To a city that once lived by nets and boats, not by hotels and terraces.

In the 1960s, when tourism began to transform Málaga forever, El Cenachero became a reminder of the old city — a link to the fishermen, the beaches where boats were pulled ashore, and the voices that once echoed through the narrow streets.

Today, visitors photograph him before boarding cruise ships or strolling along Muelle Uno. Few realise they are standing next to a worker who once fed an entire city.

El Cenachero is Málaga in bronze: salt, sun, sweat — and dignity.