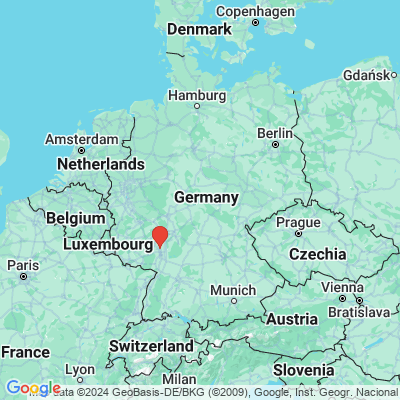

In the quiet side aisle of Trier Cathedral, beneath a swirl of baroque marble, lies a prince who once ruled not by fear or fire, but by grace. The inscription calls him “clementia alter Titus” — “in his mercy, another Titus.” His name was Johann Philipp von Walderdorff, Prince-Elector and Archbishop of Trier, Bishop of Worms, and perpetual Administrator of Prüm. He lived in a world where the Rhine was both a frontier and a lifeline, a corridor of faith and power running from Cologne to Mainz and beyond.

The 18th century was the twilight of the prince-bishops — those curious rulers who combined mitre and sceptre, and who governed both souls and streets. In the Rhineland, their territories were dotted with vineyards, abbeys, and the great palaces that embodied their dual authority. Among them, Walderdorff stood out as a man of refinement and quiet ambition. Born in 1701 into an old noble family, he rose through the church ranks to become Trier’s Elector in 1756, one of the seven men entitled to choose the Holy Roman Emperor. Yet his legacy was not in politics or war, but in the enduring beauty he left behind.

Walderdorff commissioned the lavish Kurfürstliches Palais beside Trier’s Roman basilica — a masterpiece of Rococo elegance where angels and cherubs play among stuccoed vines. He rebuilt the castle at Wittlich, improved the public roads of his domain, and founded the perpetual adoration of the Eucharist in Trier’s cathedral. His reign was gentle, prosperous, and deeply rooted in the artistic flowering of the late baroque — an age when faith still expressed itself through splendor.

When he died in 1768, his body was laid to rest in the very cathedral he had adorned. His monument speaks the language of the era: black marble veined with white, golden letters glowing under candlelight, and above it the sculpted figure of the serene prelate himself. To those who pass by, it is more than a grave — it is a reminder of a time when the Rhine valley was a patchwork of princely bishoprics, each with its own court, orchestra, and chapel, each ruled by men who saw no divide between holiness and beauty.

Walderdorff’s world would soon vanish. Within a generation, the French Revolution and Napoleon swept away the ecclesiastical states that had shaped the region for a millennium. Yet in Trier, among the stones that remember Rome and the saints who followed, his marble tomb still glows softly — a relic of an age when mercy and art walked hand in hand.

Further Reading

The Electorate of Trier and the Prince-Bishops of the Rhine – A cultural history of ecclesiastical states in the Holy Roman Empire.

The Rococo in the Rhineland – Architecture and patronage under the prince-archbishops of Trier.

Trier Cathedral: From Constantine to the Baroque – A study of the cathedral’s evolving role in European history.