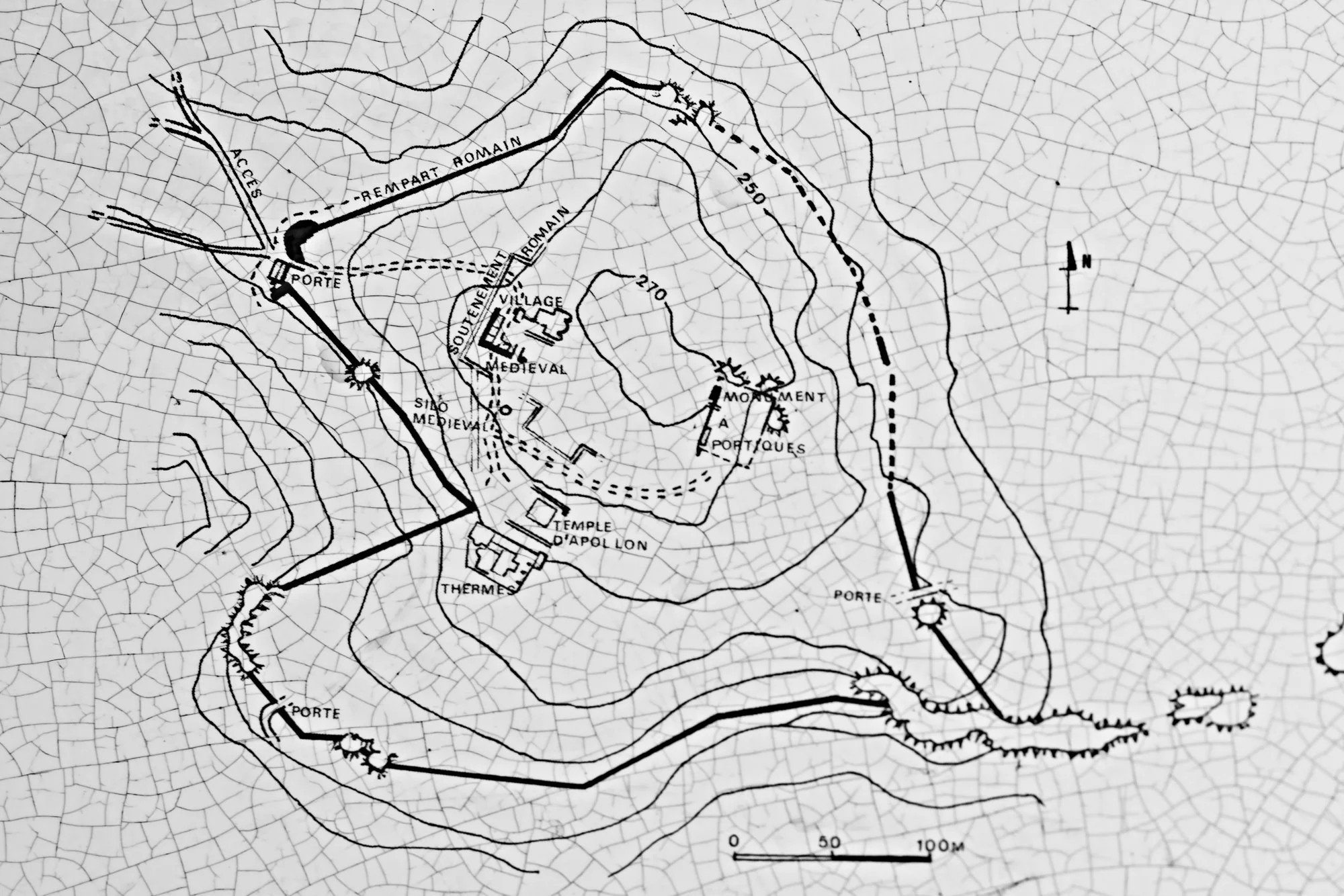

Plan of Oppidum Saint-Vincent at Gaujac, showing Iron Age ramparts, Roman monuments, and later medieval occupation layers. After J. Charmasson, published plan.

The ruins of the Roman baths at Oppidum Saint-Vincent, their low stone walls still tracing heated rooms and pools, set against the wooded hills that once framed daily life on the oppidum.

From down in the valley near Gaujac, the forested crest of Oppidum Saint-Vincent gives little hint of its past. Only when you climb it does the hill begin to speak. Saint-Vincent is not a single archaeological site, but a hillside shaped and reshaped by human lives for more than a thousand years.

The story begins around 425 BCE, when Gallic communities took possession of the summit and enclosed some twelve hectares with a defensive wall. This was an oppidum: a fortified hilltop settlement typical of Celtic Gaul. Oppida were not refuges in panic, but centres of authority, combining defense, habitation, ritual and trade. From Saint-Vincent, the Rhône corridor could be watched and controlled, and contacts reached as far as the Greek port of Massalia, modern Marseille. Archaeology reveals houses, storage areas and a striking ritual feature known as the “altar of ashes,” hinting at ceremonies that bound community, land and belief together.

By the early fourth century BCE the site was largely abandoned, its walls left to weather. But the hill was not forgotten. Around 120 BCE, as Roman power advanced into southern Gaul, Saint-Vincent was deliberately reoccupied. Its defenses were reinforced, transforming the old oppidum into a stronghold once more, now facing a new political horizon.

That horizon became Roman around 40 BCE, when Lepidus granted Saint-Vincent the status of oppidum latinum. The hilltop was reshaped into a Romanised town structured by terraces. Public life concentrated around a forum with porticoes, baths were built, and a monumental sanctuary—traditionally called the “Temple of Apollo”—dominated the sacred space. At this moment, Saint-Vincent was not merely inhabited; it was important. Its religious role drew pilgrims from across Narbonensis during major festivals, reinforcing both its political and spiritual status in the region.

The prosperity did not last. In the later third century CE, a series of earthquakes struck the region. The urban fabric of the hilltop suffered badly, and the Roman town gradually emptied. Yet even abandonment did not end the site’s usefulness.

Remains of the medieval village at Oppidum Saint-Vincent: dry-stone houses and enclosure walls built by quarrymen and stonecutters between the 10th and 12th centuries, reusing the fabric of the ancient city.

During Late Antiquity, in the fifth and sixth centuries, Saint-Vincent entered a quieter but crucial phase. Parts of the old ramparts were repaired or rebuilt using simpler masonry and reused Roman stone. These walls are often referred to as “Visigothic,” and while the term survives, it deserves nuance. Saint-Vincent did not become a Visigothic city. Instead, it functioned as a hilltop refuge, a place of temporary safety for populations from the surrounding plain in an unstable world. The walls of this period speak not of empire, but of pragmatism: repair what already exists, defend what can still be defended.

In the Middle Ages, the hill found yet another role. Around a small church dedicated to Saint Vincent, families of stonecutters and quarrymen settled on the summit. The abandoned monuments of Roman antiquity became quarries; blocks once shaped for temples and baths were repurposed for houses, walls and paths. Stone moved again, but with new meanings and new hands.

What makes Saint-Vincent compelling today is precisely this continuity through change. It was never erased and rebuilt from scratch. Instead, each generation worked with what was already there—walls reused, terraces adapted, ruins transformed into resources.

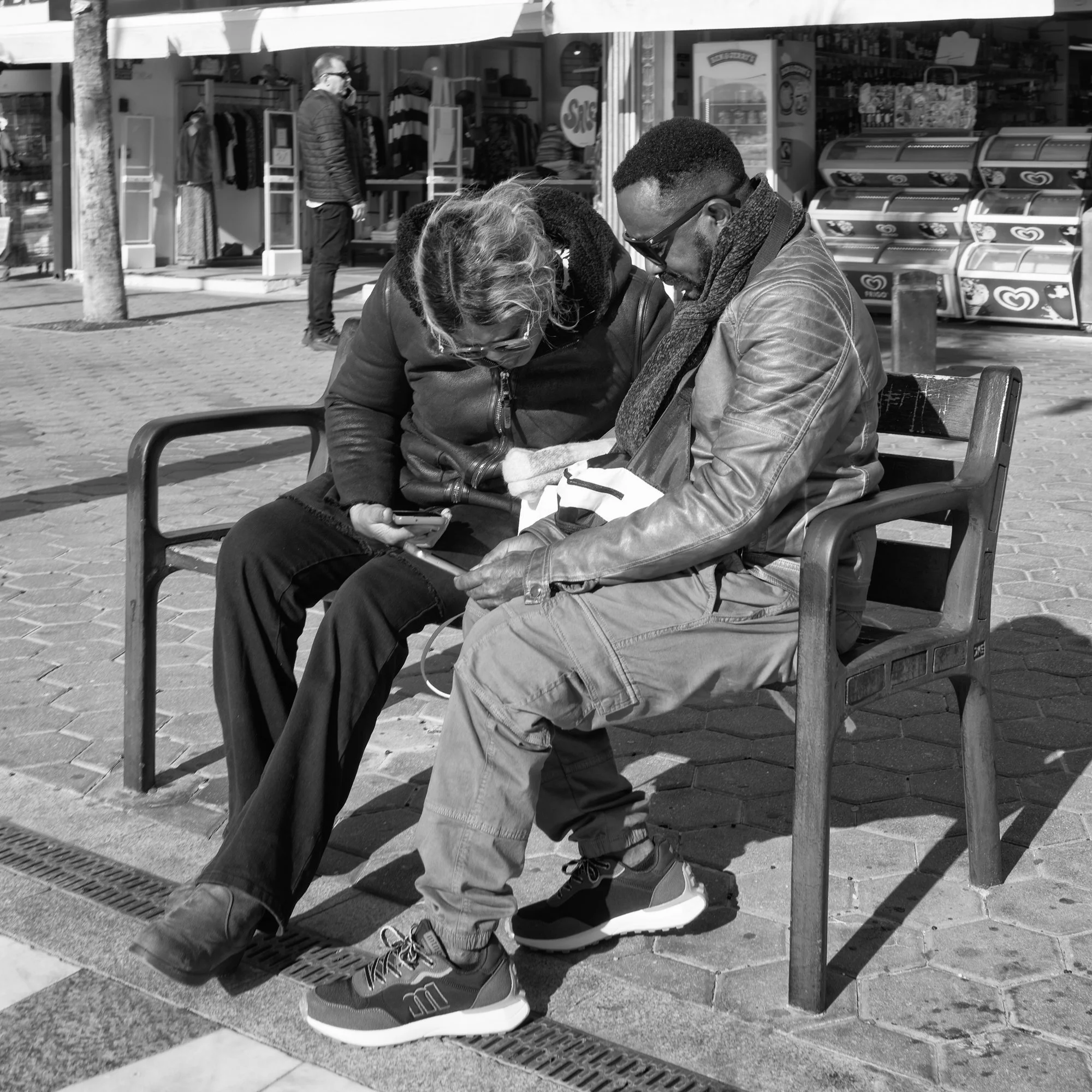

Some members of SECABR (Société d’Étude des Civilisations Antiques Bas-Rhodaniennes) enjoying lunch at the site of the Oppidum Saint-Vincent.

That layered history is why the presence of SECABR (Société d’Étude des Civilisations Antiques Bas-Rhodaniennes) matters so much. Their quiet stewardship—walking the site, monitoring erosion, sharing knowledge—continues a tradition that is as old as the oppidum itself: caring for a place because it matters. Where once councils met and pilgrims gathered, people still come together, not to defend or to rule, but to remember.

At Saint-Vincent, the walls no longer protect against enemies. They protect against forgetting.

More Information: