The Roman Theatre of Cartagena (Spain).

At first glance, Cartagena doesn’t give much away. Traffic, shops, everyday life — and then a doorway draws you inside a modern building that quietly functions as a museum. What begins as an exhibition visit slowly turns into something else.

You move upward first, not down. On the upper floor, a long, enclosed passage opens — a tunnel that leads you forward in time as much as in space. And then, almost without warning, the Roman theatre appears.

You emerge halfway into the structure, suspended between the highest rows of seats and the orchestra below. It is an unusual entrance, and a deliberate one. Rather than discovering the theatre under the city, you enter it within the city — inserted into its surviving geometry.

A stage for a rising empire

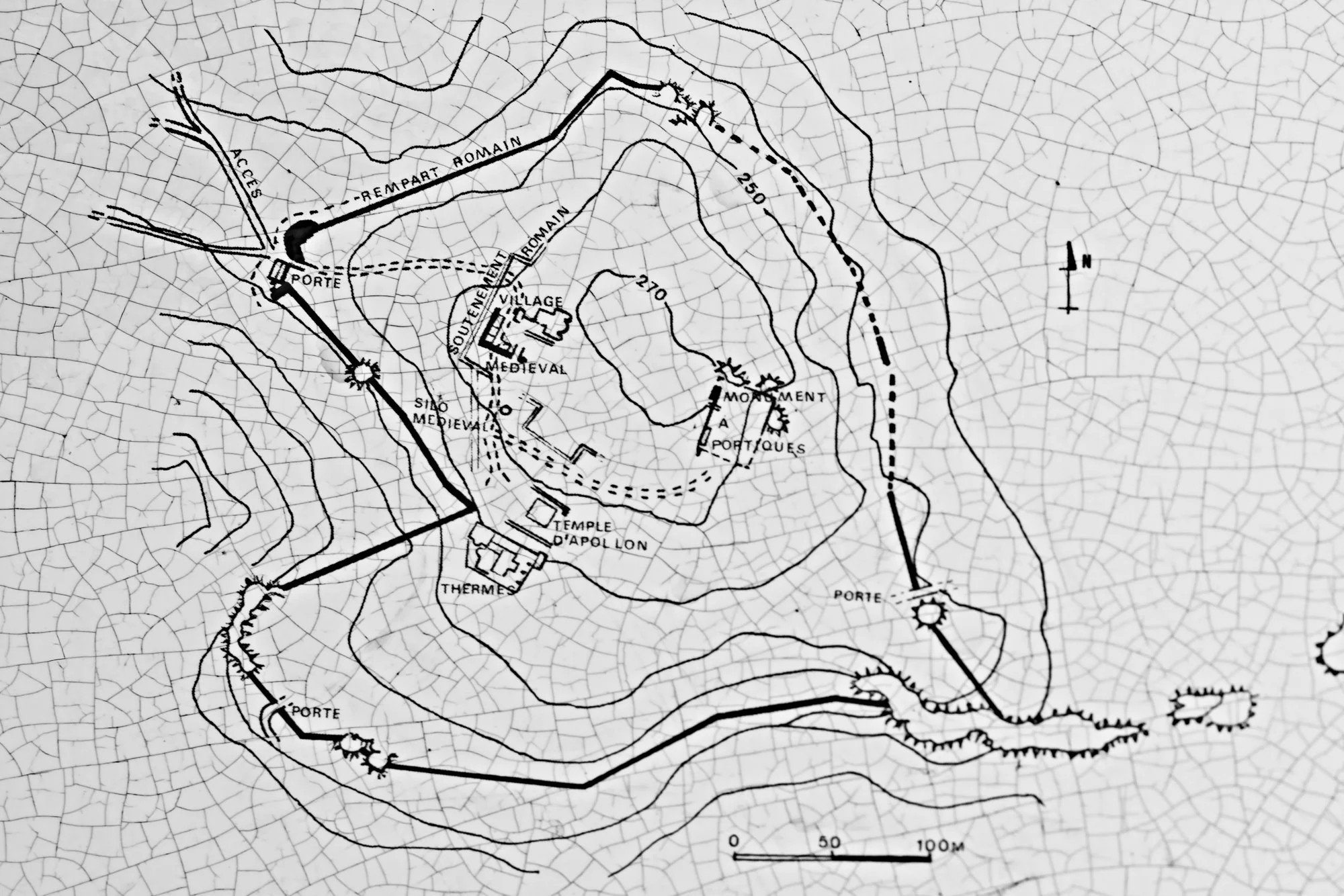

The theatre was built at the very beginning of the Roman Empire, during the age of Augustus. Its scale alone tells a clear story. This was not a peripheral town. Carthago Nova was prosperous, strategically located, and confident enough to claim a monumental public building at its core.

Roman theatres were never just places for entertainment. They were instruments of civic identity. To build one was to declare that this city belonged to the Roman world — culturally, politically and socially.

Politics carved into space

In antiquity, visitors passed beneath inscriptions honouring the imperial family before taking their seats. The message was subtle but constant: Rome was present here, watching, legitimising, ordering the city’s public life.

Inside, society was arranged in stone. The best seats lay closest to the orchestra, reserved for those whose status mattered. Architecture reinforced hierarchy long before a word was spoken on stage. Even today, standing among the tiers, that logic remains visible and instinctively readable.

Architecture that directs attention

Roman theatres are machines for focus. The rising cavea pulls your gaze downward, towards the orchestra and the stage. Movement, sightlines and sound were carefully controlled. Cartagena’s theatre still demonstrates this with remarkable clarity.

Behind the stage once stood a richly decorated architectural façade, filled with columns and statues. Performances unfolded within a setting designed to communicate order, authority and permanence — values Rome was eager to project.

Rediscovered, not reconstructed

For centuries, the theatre disappeared beneath later construction. Houses, streets and churches reused its stone and obscured its form. It was not dramatically destroyed, but slowly absorbed by the city that grew on top of it.

Its rediscovery in the late twentieth century returned a missing chapter to Cartagena’s story. Today, the museum route does not try to recreate the illusion of a buried ruin. Instead, it guides you carefully into the structure itself, allowing the theatre to reveal its scale and logic gradually.

A city that faces the sea

Carthago Nova is a Mediterranean harbour city, outward-looking and well connected. Trade, administration and wealth passes through its port. The theatre belongs to that identity: public, ambitious, confident.

What makes the visit especially powerful is the contrast. Modern buildings press close around the ancient structure. The theatre is not isolated; it coexists with the present. You do not step back into a distant past — you step into a layer of the city that still shapes it.

Rome here is not a postcard ruin. It is architecture that still commands space, attention and meaning.